With a lot of hard work and long days, my great grandfather George LeeRoy Foltz was able to lay claim to a part of the American frontier. The Homestead Act of 1862, along with its later updates in the early 1900s, had paved the way for men like him to acquire large swaths of land outright, so long as they agreed to farm and improve upon it. George and his wife Myrtle left their home in Kansas and set out for the coastal state of Oregon. After arriving in Rainier, at only 28 years old, George submitted an application in late November 1908 to homestead 4 adjoining lots of land in the high desert of Fort Rock Valley.

Right out of the gate, he encountered a snafu. Whether an accounting error, filing mishap, or by the land agent's or his own misunderstanding, his application was initially rejected two days before Christmas. The reason given was due to insufficiency of insurance, coms., and excess money. Thankfully, by the end of the following month, the proper funds were furnished, and the homestead entry #0938 was allowed to proceed.

Within six months' time, George had built a house on the property. He and Myrtle and their three young children settled into their new home on the 16th of June, 1909. What they may not have known in that moment, was that my grandfather Harry, their soon-to-be fourth child, was also moving in with them that day, having been conceived in May.

According to The Albany Citizen, the first pioneers to settle in Fort Rock had only just set up camp the year prior in 1908, so the Foltz family was truly in for an uncharted adventure. It was thought that irrigation in these parts was impossible and new scientific methods would need to be applied in order to farm anything (electricity wasn't even introduced to Fort Rock until the 1950s). The new occupiers would need to be men of very progressive ideas.

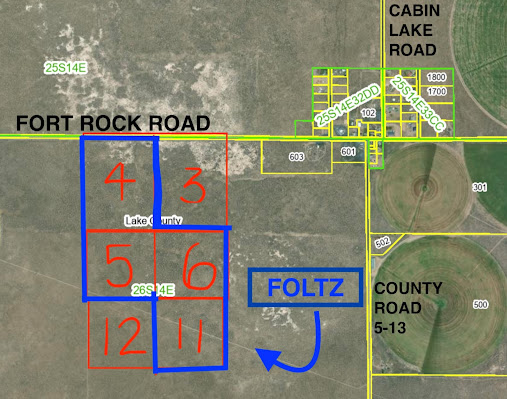

George was clearly up to the task. His land sat in the middle of an arid landscape with nothing but sagebrush for miles. His farm consisted of four lots (numbered 4, 5, 6, and 11 on the land survey) totaling 172 acres. None were timbered, and none showed any indication of coal, salines, or minerals of any kind. Lot number 4 faced the main road that ran through "town," and that's where George began developing.

In addition to building up his own property, George was also freighting for the local store full time throughout 1909. His coworker in Fort Rock was a 23-year-old man named George Harrison; yes two Georges in their 20s teaming together! When my grandfather was born on February 3rd of 1910 and formally named Ora Harrison Foltz, it makes you wonder if he was named for George's coworker. Harrison/Harry was also a given name of one of George's brothers, so there's always that possibility, too, of course.

By the end of the year, Fort Rock was "booming." The Oregon Daily Journal wrote that it had 2 stores, 1 hotel, a town hall, a schoolhouse and a post office by this time. George had managed to seed about 15 acres of rye and harvested about one-half ton of hay per acre, all on lot 4.

Unfortunately, his mother, Matilda Catherine (Stafford) Foltz, passed away on December 19th. She was still living back in Kansas and had been in ill health for many years. It was too difficult for George to leave the farm to pay his respects. This early photo of her gravesite was likely mailed to him by his siblings who were by her side when she passed.

By the end of the following year, in 1911, lot 4 proved a tad more profitable for George. He was able to seed an additional 5 acres of rye from the previous year, bringing the count up to 20 acres. He planted 40 fruit trees, and he harvested about 12 or 13 tons of hay!

His freighting duties carried on throughout this time. According to my grandfather Harry, his father would drive wagons from Silver Lake all the way up to Shaniko. The roundtrip was 4 weeks in good weather and 6 weeks in the winter months, using 6 to 8 horses. Other Fort Rock individuals in the freighting business with George were Ernie Steigleder, John Nixon Deneen, and "Shorty" Gustaffson (Helmer Gustafson of Fort Rock went by "Shorty", but I suspect it was actually Helmer's father whom George freighted alongside and must have also gone by the same nickname, as Helmer would have been far too young at the time).

George must have learned how to split his time between the farm and freighting, as he and Myrtle continued to expand their family and cultivate the land. On April 22, 1912, their fifth child, Leonard, was born. By the end of the year, lot 4 had yielded about 8 or 9 bushels per acre of rye (and there were about 15 acres), and 1100 pounds of wheat had been thrashed. Plus, 15 more acres of sagebrush was "grubbed" and cleared.

His young children were living on the land continuously, and he and his neighbors said he was there "most all of the time."

Myrtle did have to leave the homestead for a few months beginning in November on account of altitude sickness. Fort Rock is at about a 4,500 foot elevation.

But during all of these years, George steadily grew the farm to encompass a 20' by 30' painted frame house with a shingle and felt roof and front and back porches stretching 6' x 16', two barns with felt roofing (one 16' x 20' and one 27' x 15'), three sheds (one 12' x 16', one 12' x14' for wood, and one 14' x 20' for cows), a 10' x 12' cellar, an 8' x 10' hen house, at least 1 well about 30' deep with 2 pumps, a corral stretching about an acre, and 35 to 40 cultivated acres with total improvements on the property valued at about $1500 in 1913. George had also fenced in his other 3 lots with poles and barbed wire.

While no record exists explicitly stating the number of animals on his ranch (the 1910 agricultural schedules were destroyed by government order), the type of livestock George raised in Fort Rock can be inferred from the variety of buildings he constructed on the property. It's likely he had several chickens and maybe a handful of cows. His corral implies he had horses, but that can also be substantiated by photo evidence of his freighting ventures.

"Well Myrtle I am still alive the horse is lame yet I brought sum men over hear with the little team Madress I will let you now when I lead. Rite to Madress + Bend. Pappa"

Plus, his son Harry claimed his dad had a lease worked out with the Express Company for their stages to change horses at his place. This would have more than likely been in reference to either The Bend, Madras & Shaniko Stage Company (which the above postcard shows him working with) or the Wells Fargo & Company Express which had bought out many of the stagecoach express routes in the West.

Harry's daughter Sandra remembers a time when the family went down to Texas to visit with Harry's older brother Lee and she heard about this express company. "...I was so enthralled and privileged to go with my dad and Uncle Lee to the Cadillac Bar in Laredo, the only air-conditioned place, where they had a beer and I had a rare coca-cola. They exchanged some very funny stories about living on their farm in Fort Rock. I was just glued to their conversation and sometimes shocked. One story was about how the brothers would hide in the bushes when the stage came in and watch the ladies get off to relieve themselves outside. And they would just guffaw as they told these stories and I could see they were having a great time reminiscing."

Harry's dad George would not be able to capitalize on this business for long, though, as the federal Parcel Post Law, passed in 1913, enabled the U.S. mail system to begin carrying small packages. This cut into the express companies' profits, especially since the U.S. postal service was able to utilize trains to speed up portions of their delivery routes.

On March 27th, George filed a notice of his intention to finalize his claim on the land. He went into the land office with at least two witnesses, Thomas H. Brady of Fort Rock and Ivan E. Beeler of neighboring Fremont, who vouched for his work on the property.

George's application also mentioned witness testimony from two other associates, lumber industry logger David A. Busch of Fort Rock and rancher William F. Menkenmaier of Fremont. But if those two men submitted affidavits to the commissioner, their documents did not remain on file with the entry held in the National Archives.

Menkenmaier's son, George Earl, became well known around the Fort Rock Valley. His property (later sold to Reub Long) included what is now known as Cow Cave, or the Fort Rock Cave, where the oldest dated, indigenous-made sandals in the world were discovered. They were dated to be more than 9,000 years old. And there were 70 pairs of them!

The final homestead certificate was issued on April 1st. George signed over the title to his wife Myrtle in July in consideration of $10.

In true government fashion, the patent took a few more months to officially be proven, printed, and filed. It was transmitted to the local field office on August 19th of that year and mailed out by September 26th.

It was a multi-year commitment, but by 1913, George could say he achieved his goal of homesteading in the West. Unfortunately, at this time, there's no further record of George's successes or failures on the land. Many of Fort Rock's early settlers struggled to keep their farms going long-term. The high desert just didn't cooperate even with their dry farming techniques, and many gave up and moved on to more promising efforts elsewhere. The local jackrabbit population devouring all the crops they did manage to grow didn't help either. Sadly, the Foltz family also succumbed to this realization.

Modern weather analysis on the Fort Rock Valley now shows those years to have gone through a significant dry spell. Current farmers in the area, using 21st century technology and deep well irrigation, have turned to the successful production of alfalfa, and aerial views of the region boast large, and very green, crop circles.

It's unclear as of yet when exactly George gave up on the Fort Rock property, but by September of 1915, he had moved his family up north around Pendleton, Oregon at the southern end of the Umatilla Reservation near St. Andrew's Mission. He continued farming there until 1918, when they moved to Walla Walla, Washington.

Although this may have been seen as a failure at the time, it's quite possible the move north saved some of the Foltz family's lives. When the 1918 "Spanish" influenza epidemic hit, the city of Walla Walla came away unscathed, but the citizens of Fort Rock, Oregon were severely impacted. Shockingly, there was only one recorded death in their ranks, but nearly everyone in the valley fell ill. George, Myrtle, and their kids were spared from that risk.

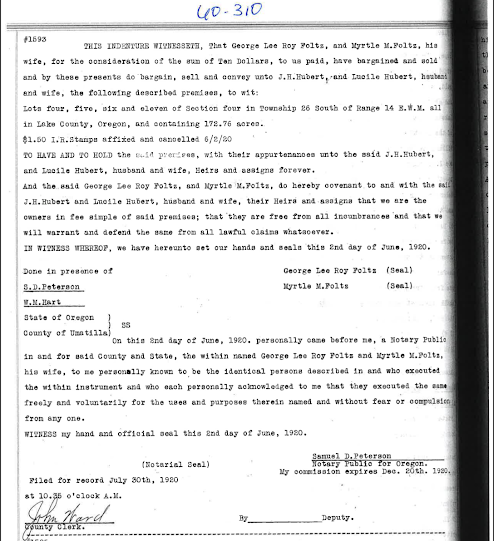

A couple years later, in June of 1920, George and Myrtle finally sold off the Fort Rock property, all 172 acres of it, to Jack and Lucile (DeHaven) Hubert, for a total of $10.

For the past 5 years, Fort Rock had no longer been the Foltz family's permanent residence, so it's impossible to know what kind of condition they left it in.

However, one indication that the Huberts may have also found Fort Rock to be inhospitable, was the fact they were living in Washington State just 4 years later. Though, it's possible they never moved onto the land in the first place.

The Foltz family's Fort Rock homestead now sits on Tax Lot No. 600 which consists of 16,825 acres (as of 27 July 2023). According to the Lake County Assessor's Office, it's now all public land, managed by the federal Bureau of Land Management.

It came back under possession of the United States in June of 1940 by warranty deed from Jack and Lucille Hubert in consideration of $172.00 ($1 per acre). Hubert certainly made a profit on that transaction! It's amazing to consider that those 4 lots were only ever occupied by 2 families over a period spanning less than 4 decades.

Interestingly, the Huberts and Foltzes did business with each other over another piece of land in Oregon, as well, this one in Umatilla County. Once more, Jack paid George $10 for his property. It would be fascinating to know if he made out like a bandit on this lot, too.

In 1967, George's son and grandson drove through Fort Rock to see the remnants of the unique homesteading town. Unfortunately, not much remained. It was quite literally a ghost town. They filmed portions of the buildings still standing (none of which included the home where Harry was born in 1910), a signpost at the location of Beeler's Well, a broken down windmill, and the pioneer cemetery:

They stopped by Reub Long's ranch (the old Menkenmaier property -- unbeknownst to them at the time) and walked through his barn. My dad recalls Reub getting cagey when they asked about his branding iron collection, of which, he had amassed quite a few.

Harry was interested in knowing if Reub had perchance come into possession of the Foltz brand, which resembled the last two letters of their name, T and Z, welded and merged together at the top. He vehemently denied it and quickly, too, but my dad remembers there being so many irons in the barn, he felt there was either no way for Reub to know exactly what all he owned, or he wasn't in the mood to let any of them go if he did.

Reub had co-authored a book titled The Oregon Desert. He gave them a copy and signed it:

"July 28 - 1967 To Harry Foltz. An old timer born on a homestead on the desert in 1910 this book will bring many memories R. A. Long"

Then, Harry and my dad headed up north to visit Myrtle, who then lived on her own in a multi-resident apartment building in downtown Walla Walla (George had died back in 1923 when Harry was only 13 years old; Myrtle had remarried twice after, but was widowed and divorced from those two unions).

Harry and my dad left the book with her overnight that Reub had penned, and by the following morning, she had read it cover to cover. She jotted down the following list of observations; the most interesting being about Harry needing his wrist wrapped up by Dr. Thom in Silver Lake after he fell into the entrance of their cellar (Dr. Thom had been the only attending physician to the Fort Rock residents during the flu epidemic):

There is now a Homestead Village Museum in Fort Rock which pays tribute to this era of high desert pioneers. The museum is open for long weekends throughout the summer months. Many buildings that were falling into disrepair and were under threat of being burned down in the surrounding valleys have been relocated to "downtown" Fort Rock for all to visit. There's been much history lost to time, but despite the failed homesteads of the past, many Oregonians retain a passionate fervor for the original Fort Rock settlers and what they tried to accomplish there.

"The courage and pluck of that little family, fighting a losing battle against insurmountable difficulties, were inspiring. They were people who would fight to the last without complaint, and blame no one if they lost. There were many others like them in the homestead country, the sort of people who have formed the foundation and backbone of our American civilization. Nowhere else have I seen such exemplification of the brotherhood of man as I witnessed in the homestead country. Everyone was always ready and willing to help his neighbor, or anyone whose condition was worse than his own, without expecting any compensation, even if it exhausted his last resource."

- Dr. Urling C. Coe, Bend's first doctor

Sources:

Raymond R. Hatton, Pioneer Homesteaders of the Fort Rock Valley (Portland, Oregon : Thomas Binford, 1982).

E. R. Jackman and R. A. Long, The Oregon Desert (Caldwell, Idaho : The Caxton Printers, Ltd., 1966).

https://www.midcontinent.org/rollingstock/dictionary/express_companies.htm

https://archive.org/stream/historicresource00godf/historicresource00godf_djvu.txt

https://richbergeman.zenfolio.com/

https://fortrockoregon.com/

https://photos.salemhistory.net/digital/search/searchterm/Fort%20Rock,%20Oregon/field/subjec/mode/exact/conn/and/cosuppress/

https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Lake_County,_Oregon_Genealogy

https://www.lakecountyor.org/index.php

https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/records/county/Pages/lake-inventory.aspx

http://www.trainweb.org/highdesertrails/bslco.html

https://www.oregonhistoryproject.org/articles/historical-records/shevlin-hixon-mill-bend-oregon/

https://www.pediment.com/blogs/news/hello-bend-location-highlight-old-mill-district

https://www.oregonhistoryproject.org/narratives/central-oregon-adaptation-and-compromise-in-an-arid-landscape/industrial-period-1910-1970/the-mills/

https://www.oldmilldistrict.com/about/history/#:~:text=The%20first%20of%20the%20big,complex%20upstream%20from%20Mill%20A.

https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/fort_rock_sandals/

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment